|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

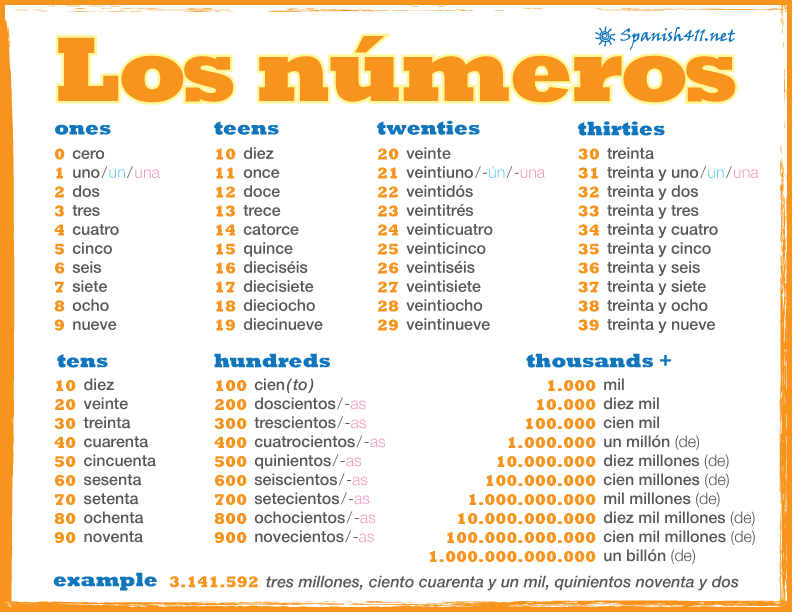

Numbers in Spanish

Want a quick answer? Let’s start with the good news: there is (almost) no difference between the way that we write numbers in Spanish and the way we write them in English. The bad news is that when we use numbers in conversation, they definitely aren’t pronounced the same way. But whether you’ve picked it up from “Sesame Street” or “Dora the Explorer” you probably already know at least a handful of Spanish numbers. Keep reading to learn more. Cardinal NumbersA “cardinal number” is just a fancy term for a numbers we use in counting things (or indicating times, dates, or ages). Let’s take a trip through the Spanish cardinal numbers from cero (0) to un trilión (1,000,000,000,000,000,000) noticing some interesting quirks along the way. Fun Fact: Cinco is the only Spanish number with the same number of letters as the number it represents. The first 10 numbers (as well as zero) all have unique names:

The next five also have unique names:

Note: There are two acceptable options for writing the numbers 16 through 19. The “old-school” way is to say “ten and six,” “ten and seven,” etc. The newer method is to combine those words into one word. At that point the “z” in diez becomes a “c” and the “y” becomes an “i.” Both versions are pronounced the same way. The shorter word is preferred nowadays. After that the numbers come in combinations. You are literally saying “ten and six,” “ten and seven,” “ten and eight,” etc.:

Veinte means “twenty” and from that point on the pattern is very similar to sixteen through nineteen; you are literally saying “twenty and one,” “twenty and two,” etc.: Note: Once again it is also preferable to condense these

numbers down to one word by replacing the trailing

After veinte comes treinta and the same pattern is followed: Note: After the twenties we no longer condense our numbers into one word.

All of the numbers in the forties, fifties, sixties, seventies, eighties, and nineties work the same way as in the thirties:

Technically ciento means “one hundred” in Spanish, but its shortened form, cien, is preferred when there are exactly 100 of something:

You may notice there is no longer any “y.” This is because the “y” is only used to separate the 10’s place from the 1’s place. If there is nothing in the 10’s place, we don’t use “y.”

Note: The plural of cien is cientos (not cienes.) Ciento is followed by:

“One thousand” in Spanish is mil. And we don’t say un mil; it’s simply mil:

After the thousands comes the 10’s and 100’s of thousands: Note: In compound numbers, use ciento if the number that follows is smaller than 100. Use cien if the number that follows is larger than 100.

Next, a thousand thousand is a million or un millón. When we have more than one million, millón becomes millones:

Note: This is not actually so much of a difference in languages as it is a difference in ways of counting very large numbers. Historically there is some disagreement even between English-speaking countries as to what exactly “billion” represents. Bonus: see Long and short scales Now things get a little weird. Adding three zeros to a million in English gets us to a billion. But in Spanish it’s a mil millón, or a thousand million. This throws the rest of the chart out of synch with what we might expect as well:

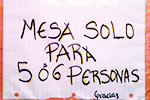

Cardinal Numbers as AdjectivesStill have questions about numbers? Try out the Spanish Number Translator If you’re simply counting numbers (like in “Hide and Seek” while your friends are hiding) the list above is accurate. However, much of the time when we use a number we follow it up with a noun, e.g. “six cars,” “24 tables,” “38 houses,” etc. When we do this we’re actually using the number as an adjective and some interesting things need to happen. First of all uno gets shortened to un when it comes before a masculine noun, and likewise numbers ending in -uno are shortened to -ún (note the accent mark). Ciento is also shortened to cien when we’re dealing with exactly 100 of something. For example: un coche cien coches Secondly, as with other adjectives, we need to make our numbers agree in gender with the nouns that they modify. However, this only happens with numbers ending in -uno and words ending in -ientos (all of the “hundreds” words from 200 to 900). For example:

Every part of a number that can agree with the gender of the noun should agree. For example 654,321 tables would be written out as seiscientas cincuenta y cuatro mil trescientas veintiuna mesas. Lastly, numbers that end in millón, billón, trillón, etc. are followed by de: un millón de casas Decimal Points and CommasYou may have noticed the strange looking decimal points in the right hand column above. This is not a typo. The majority of Spanish-speaking countries do the opposite of English-speaking countries when it comes to decimal points and grouping thousands: commas are used for decimal points and periods are used to separate the groups of zeros. The number “21.7” would be written “21,7” in Spanish and would be read veintiuno punto siete. Ordinal NumbersWhile we use cardinal numbers to count things, we use “ordinal numbers” to put things in order (such as the order in which runners finish a race). Here are the Spanish ordinal numbers:

FractionsWe express Spanish fractions the following way:

From “fourths” to “tenths” we simply use ordinal numbers. From “elevenths” to “twentieths” we use cardinal numbers with the suffix -avo. Beyond “twentieths” we simply use an ordinal number with the word parte. E.g.: un trigésimo parte. MultiplesNote: Multiples can also have masculine and feminine forms: cuádruplo, cuádrupla. We use “multiplicatives” to make multiples out of a number. Spanish multiples are similar to the English:

PercentagesPrecentages are written the same way in Spanish as they are in English. The word “percent” is por ciento in Spanish.

Notes

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This work by Spanish411.net is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This work by Spanish411.net is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. |